Question Key

The content video described different ways to think about how to

define a species. With the next four questions, let’s think about why

there are so many different species definitions and what the

consequences are of choosing one versus another.

-

What’s the common idea that underlies the different methods of defining

species? That is, what we might think of as a basic way to explain what

we mean when we say that two organisms belong to different species?

Reproductive isolation is

the underlying idea here. When we build phylogenies and think about what

we mean by defining something as a species, we have this idea that a

good species will be on its own evolutionary trajectory, separate from

other species. That means that it is reproductively isolated from other

species – it is not exchanging genetic information. This is built into

the way we create phylogenies – we define relationships based on genetic

similarity due to shared ancestry.

-

Why is it so hard to define a single species concept that works in all

cases? Why might it matter what species concept we choose to apply?

Multiple reasons that this

is hard! One of them is that speciation is a process, it’s not a binary

switch, it rarely happens in one defined step or point in time. (The

exception to that, of course, is that polylploidy can create a new,

reproductively isolated species in a single generation.) Two populations

of one species can be separated from each other and may eventually

become different species, possibly unable to interbreed, but there will

also be a (potentially long) period when they are able to interbreed and

there may still be gene flow between them, even if they look or behave

very differently from one another.

Another big issue is that

evolution of sexual taxa and that of asexual taxa can be rather

different. Reproduction is how we define species that are sexual since

different individuals bring their genetic information together to create

new individuals. But in non-sexually reproducing taxa, like bacteria,

this does not happen. So should that mean that every single bacterium

represents a separate species since it doesn’t exchange genetic

information with another bacterium? Clearly not! And, though they don’t

use sexual reproduction, bacteria do have mechanisms for exchanging

information (horizontal gene transfer). One thing we can see in common

between sexual and asexual taxa is the thread of genetic similarity – we

still use this criterion in the case of bacteria to define species.

Along the same lines, in some groups of taxa, hybridization between

somewhat distant species is not unusual (happens a bunch in plants) and

might in fact act as a mechanism for creating genetic variation. So we

have to think carefully about what horizontal gene transfer and

hybridization mean in any given example. Note that horizontal gene

transfer and hybridization might be “common” at the evolutionary scale

of many generations and populations while still being fairly uncommon at

the level of how likely this is to happen to any particular individual

of that species.

-

The process by which new species evolve, speciation, is commonly divided

into two general types: allopatric speciation and sympatric speciation.

-

What’s the difference between sympatric and allopatric speciation? Why

do biologists think this matters?

Allopatric speciation is the

process when two populations diverge into different species while living

in separate areas, not overlapping in geographic range (allo =

different, patry = fatherland). Sympatric speciation is when two

populations become difference species but live in the same or

overlapping geographic ranges (sym = same, patry = fatherland).

Biologists care about this because gene flow (hybridization) between two

incipient species (beginning to become different) can occur much more

easily when the two groups are found in the same spaces. So, speciation

seems more likely when the two groups are living in allopatry compared

to sympatry. Enough of a reduction of gene flow to allow the two groups

to become reproductively isolated seems much more difficult to achieve

in sympatry compared to allopatry.

-

What evolutionary forces are most important in each type of speciation

(sympatric and allopatric)?

Remembering the evolutionary

forces we’re thinking about are: mutation; nonrandom mating; genetic

drift; gene flow; selection. We won’t consider mutation much as it’s a

slow process and not so different between allopatric and

sympatric.

Allopatric: genetic drift

and gene flow will be critical. In particular, genetic drift is likely

to be the main driver of differences between group A and B living in

different places. In addition, anything that reduces the rate of gene

flow between A and B will also be critical here, allowing for greater

change due to drift. Selection may also help to differentiate A and B,

IF they live in environments that have different selective pressures

(such as differences in salinity, precipitation, altitude).

Sympatric: Because there

will likely be more gene flow than if A and B were separate, genetic

drift likely won’t contribute much to making A and B different from each

other (b/c they are still connected by too much gene flow). More likely,

nonrandom mating (favoring mating with individuals from the same group)

will be important in creating barriers to reproduction. Similarly,

selection which favors mating with individuals from the same group will

also aid in creating barriers to interbreeding, thus allowing speciation

to occur. However, any ongoing gene flow can erode the differences

created by nonrandom mating and selection, making it less likely that

speciation happens. Selection will have to be strong to overcome gene

flow’s effect.

-

What makes sympatric speciation controversial?

Many biologists have felt

that it’s nearly impossible for nonrandom mating and selection to be

stronger than the effects of gene flow. In part this is because when A

and B do evolve to be different from each other, in order to continue to

be species into the future they probably need to be unable to mate with

one another. However, this is likely to require a lot of time to occur…

populations will have to have the “right” mutations arise that cause

incompatibility. To add to the problem, the general sense is that

nonrandom mating and selection tend to be things that occur for

relatively short timescales compared to something like gene flow. So, if

the environment changes in some way and the source of the natural

selection (that favored different phenotypes in A from those in B)

disappears, gene flow will quickly cause the collapse of A and B back

into a single species.

Other biologists question

whether the complete cessation of gene flow is necessary for speciation

to be considered complete. This is partly based on the observation of

gene flow being possible even between many species that are not

especially close relatives, without that causing them to lose their

species identity. There is a lot of debate about how much gene flow is

enough to prevent speciation (or to maintain two groups as one

species).

-

With some frequency we find what appear to be well-defined species (they

look or behave very differently) that are capable of and in fact

experience some level of gene flow. Give a hypothesis for why some pairs

of closely-related species can produce hybrids while others cannot.

There are mutliple possible

reasonable responses. Here are a few examples:

Closely-related species that

happen (by chance) to have evolved so that they are genetically

incompatible will not be able to produce fertile hybrids. This could

happen due to a change in the structure of chromosomes so that

homologous chromosomes can no longer pair up correctly during

meiosis.

If two closely-related

species live in the same or nearby areas but reproduce at different

times of year, then there is no benefit to evolving to avoid breeding

since they won’t end up encountering each other during a breeding

season. Thus, they may be inter-fertile. However, if breeding is

possible, it could be favorable to avoid breeding with the other species

(if that reduces number of offspring or their survival), and thus

individuals that did avoid inter-breeding would have an

advantage.

Another possibility is that

some species might be genetically compatible (such as having the same

number of chromosomes) but perhaps their reproductive structures have

evolved such that it’s not possible for fertilization to occur unless

the male and female have physically compatible structures. In other

species, this difference may not have arisen, allowing for hybridization

in some cases and not others.

For the next three questions, we’ll focus on a couple of graphs

demonstrating logistic growth. The content videos discuss the idea that

logistic growth occurs when a population can’t keep growing at the

maximum possible rate forever because of factors like limited resources

or increasing numbers of predators. Because the rate of growth slows

down as the population size increases, logistic growth is a form of

density-dependent growth. By describing the growth as density-dependent,

we can test for limitations on growth without having to observe

population size over long periods of time. Instead, we can measure

growth-related traits for a species in populations that have differing

densities. To think about what this means—and what a density dependent

pattern looks like, use the figures below to answer the following

questions.

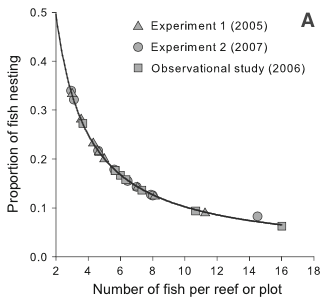

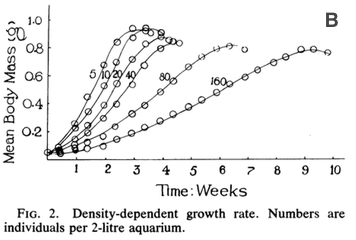

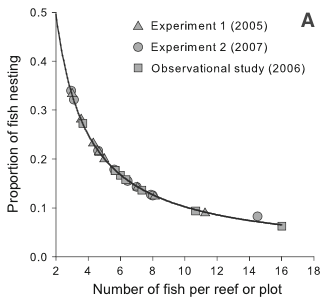

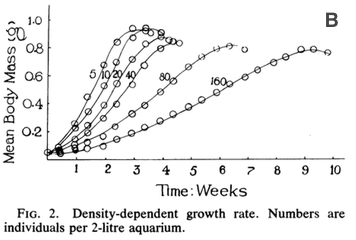

Figure 1. Measurements of density dependence in (A) populations of

bridled gobies (a fish) and (B) Rana tigrina tadpoles.

-

Figure 1A shows data collected from natural populations of the bridled

goby, a coral reef fish that exhibits density-dependence.

-

Describe the relationship depicted in this graph (specify the axes and

how one variable changes with the other). Exactly what is it that tells

us density-dependence is occurring?

-

What do you think the graph would look like if there was not

density-dependence?

In Figure 1A, we see that

the fraction of the goby population that is nesting (y-axis) changes

depending on how many fish are present on the reef or plot (x-axis). As

the number of fish on the reef increases, a smaller fraction of the

population are actually nesting. So, probability of reproducing is

negatively correlated with population density.

If there was not density

dependence then most likely the proportion of fish nesting would not

change as number of fish changed. The line might be flat – so there

would always be 25% or 50% (or whatever value) of the fish building

nests and reproducing. This would mean the rate of reproduction was not

dependent on population density.

Figure 1B also depicts density-dependence, measured experimentally for

Rana tigrina tadpoles.

-

What is the relationship depicted here? How can we tell that there is

density-dependence?

-

What would the graph look like if growth was not density-dependent?

In Figure 1B, the curves

form something like an S-shaped curve BUT that’s not what tells us about

density-dependence, as we can see if we look carefully at the graph.

Here, each of the lines on the graph is a separate tank that contains

tadpoles where each line shows tanks with a different number of tadpoles

(from 5 to 160). Because the aquarium tanks are all the same size

(2-liters), tanks with more tadpoles have higher density. The y-axis is

the body mass (size) of the tadpoles while the x-axis is time. Thus, we

are seeing how the rate of growth of tadpoles changes across time in

response to density. To see whether there is density-dependence, we need

to compare the lines that represent different densities. We see that in

the lowest density tank (5), tadpoles reach a maximum size (perhaps when

they metamorphose to frogs) after 2-3 weeks. But in the highest density

tank (160), the tadpoles reach max size after a longer time, around 9

weeks and at a smaller body mass. This change is what signals to us that

there is density dependence for growth rate.

If growth rate was not

density-dependent, then we’d expect all the growth curves to completely

overlap – they would all grow at the same rate, reaching the same max

size and at the same time.

So you’ve probably noticed that Figures 1A and 1B have different axes

than are usually used to plot the S-shaped logistic growth curve. The

thing is, the logistic growth curve itself (with x = time and y =

population size) doesn’t actually tell us anything about the underlying

change in the population that leads population growth to slow down as

density increases. But Figures 1A and 1B address this issue. Gobies and

tadpoles achieve slower rates of population growth in different ways.

How does it happen in each case?

For gobies, the fraction of

the population who are attempting to reproduce (build a nest) decreases

as the density of the population increases. This should relate to the

birth rate such that a larger population will have a lower birth rate

(babies born per individual in the population). This could be happening

simply due to the number of nesting sites available in the breeding area

(there is a set number of possible places to build a nest), which would

limit reproduction even if there were plenty of food resources.

When living in a denser

population, tadpoles grow slower. In this case, that’s likely to be due

to food limitation. And, tadpoles can’t reproduce until they

metamorphose into frogs and reach maturity. So, slower growth as a

tadpole is likely to mean lower birth rates in the population at large

(also, number of offspring is often correlated with size so if they are

smaller at maturity in dense populations, then each frog likely has

fewer babies).

It seems obvious that organisms are likely to experience

density-dependent growth (resembling the logistic curve), but what about

exponential (density-independent) growth? We do observe populations in

nature that exhibit this kind of growth — can you think of examples?

Since growth does not slow as population size increases, what prevents

exponentially growing populations from over-running the world?

In exponential growth,

populations grow at their maximum rate, regardless of resource

availability – that’s often because resources are likely to be unlimited

when this is happening! While those populations would have to slow

growth as resources were depleted, other factors may intervene before

that point is reached, thus allowing some species to constantly grow at

their max rate. For example, events like fires or floods can cause very

high mortality that is not related to the population density but just

related to luck and the livability of the habitat. When this is the

case, organisms can always produce the max number of offspring as

quickly as possible and thus grow exponentially.

While some species are able

to adjust how many offspring they have per reproductive attempt, others

cannot and thus must respond in different ways. For example, bacteria

that are dividing by binary fission will necessarily always produce 2

daughter cells (offspring). They can’t produce more and they can’t

produce less. So how can they adjust reproduction rate? By the length of

time between cell divisions (reproductive events). So, in organisms like

bacteria it’s especially important to measure rate of reproduction per

unit time.

So what happens to

exponentially growing species when they do use up the resources? In many

cases, these species will have already reproduced to make offspring that

can disperse to a new habitat where resources will once again be

abundant. The parent organisms then finish out their lives in the

original habitat patch. Invading or colonizing a new habitat patch is

crucial to the spread of many taxa that we would describe as growing

exponentially. They are also referred to as colonizing species.

Consider life history strategies, the extremes of which we sometimes

describe as “r- selected” or “K -selected”. What do these terms mean?

How are they useful in thinking about the variation in life histories

that we see in nature?

The terms “r-selected” and

“K-selected” refer to the way in which populations of these species tend

to grow – either very quickly at a high rate (“r-selected”) or more

slowly and reaching a stable size (“K-selected”). If we look at slide 4

in the Life History video lecture, we can see that there are many life

history traits that we think of as correlated with growing super fast

versus a slower but more stable growth rate.

This dichotomy can be useful

for thinking about what factors influence how quickly a population is

able to grow or how well it can move to find new habitats. But it’s

important to realize that in reality a species might exhibit a mix of

these traits, not all r or all K type features. For example, an oak tree

will grow slowly and have a long lifespan BUT it will also produce TONS

of offspring (acorns) in its life and they are relatively small compared

to the size of the tree itself.